*Editor's note: This story was edited before its digital publication to correct some errors with time frames.

On March 13, 2020, then-President Trump declared a national emergency over the COVID-19 pandemic. Lockdowns and stay-at-home orders began, and most everyone would soon find themselves wearing a mask.

For students preparing to head off to high school in the following school year, it was a disruption to their education which would end up looming large over their final years of secondary education.

In June, the Class of 2024 graduated, and teachers and faculty members saw students who spent the entirety of their high school years grappling with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The disease majorly altered how these students experienced what are commonly considered some of the most formative years of growing up.

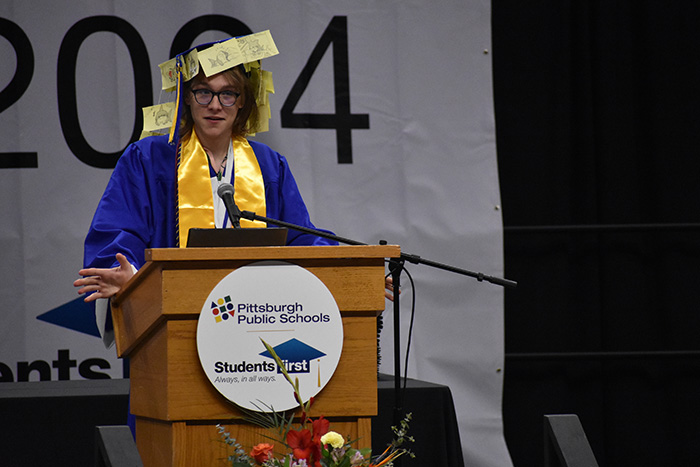

“We’re the only class in history to graduate with three years (of high school),” said Demir Frison, valedictorian and senior class president of the Perry Traditional Academy Class of 2024, in a speech during the school’s commencement ceremony on June 14.

While Frison insisted his address to the class wouldn’t be a “COVID speech,” the pandemic did figure into many of his remarks. He recalled the feeling of not seeing any of his fellow classmates’ faces as they all attended class remotely, or even hearing their voices because “literally nobody unmuted their mics.”

He compared the students’ situation to a grasshopper in a mason jar. Whenever a grasshopper is first placed into such a jar with the lid shut, it will repeatedly attempt to jump out, slamming against the lid every time. Eventually, the insect will stop trying to jump, continuing to do so even once the lid is removed.

Frison encouraged his fellow classmates to push past the difficulties and obstacles they’ve faced through their years at high school.

“We have overcome too much to not explode out of our mason jars,” he said.

A student’s perspective

Phineas Sawyer, the salutatorian of the Perry Class of 2024, has a relatively unique experience with COVID-19 as it pertains to high school. He spent his first two years of learning during the pandemic at another school, coming to Perry during the 2022-23 school year.

Sawyer sat down with The Chronicle to share his high school experience, and what he thought of dealing with the pandemic’s impacts on his education.

“High school, the best way I can explain it, is the most mixed bag you can get with a thing,” he said.

Sawyer felt he was able to get the education he needed out of Perry, even in the face of online classes and disruptions to the school year. However, he felt he missed out on the “other side of what high school is supposed to be.”

“Interacting with people,” he said. “I think that’s what took the biggest toll.”

He felt that the fact students didn’t need to have their cameras on during online classes made people less likely to talk. Even once students returned to in-person education, he felt the presence of masks made everyone “recede in.”

Sawyer also acknowledged the challenge that came with online classes. He said he struggled to do his work “as efficiently and as well” as he thought he could due to struggling with the online format, calling it a “whole song and dance that a lot of times no one knows how to do.”

His time in high school also saw the elimination of a longstanding school experience: the snow day. With schools now having robust online options, cancellations due to bad weather are a thing of the past in virtually all school districts, something Sawyer doesn’t necessarily feel is a good thing.

“I get it from a district standpoint, because you have to get those X amount of days in,” he said. “But I feel like you lose what makes those days special. It’s a snow day, it’s canceled and everyone can just enjoy this thing that happened.”

Now, he said, students still have to get ready early and worry about whether their teachers posted the correct links for class and so on.

“It becomes this stressful day instead of what it’s supposed to be,” he said.

Still, while Sawyer acknowledged there were parts of high school he hated, he said there were also things he’s going to miss.

“The people, the routine,” he said as examples. “Once you had a routine for 13 years of your life through your developmental stages, it’s a big shift.”

From a teacher’s side

When schools started shutting down for online classes, Jason Boll, who teaches English for ninth and 11th graders at Perry, knew that his students were about to face a monumental obstacle to their education.

“I remember thinking that while kids are wildly resilient, they’re not going to be OK here,” he said. “This is a really difficult position we’re putting them in.”

Boll said so much was lost in the transition to virtual classes. While much of education these days may be measured in test data, Boll feels the way he interacts with his students and they interact with others is equally important, as it provides a way to “pick up intricacies in the human experience” and identify how best to help his students.

Such a thing isn’t possible, he said, when all he sees of his class are “small, Brady Bunch-style squares” on a computer screen.

“We learn through discussion and conversation and experiences we can create, more so than worksheets and rote memorization,” he said.

“It was almost entirely impossible to create discussions in a virtual setting,” he added later.

And while the height of the pandemic may have passed, Boll feels there are long term ramifications ahead. Attendance has become a major problem, and Boll believes school is “taken less seriously” overall.

“It’s not like attendance was perfect before the pandemic, but across every sector of schooling, attendance has majorly decreased,” he said.

Beyond the students, the pandemic also took its toll on teachers. Boll said the switch to virtual classes made him realize how much he liked his job in “its traditional sense,” and how much he doesn’t like the current direction.

“I lost my favorite part of the job, which is teaching in front of a class,” he said. “What I did during the pandemic, I wouldn’t consider it teaching.”

The Chronicle also spoke with Julie Urbanek, a math and art teacher at Passport Academy Charter School, about her experience. Urbanek is a Northside resident, living in Brighton Heights.

Urbanek described the initial months of COVID as “very difficult and stressful” as teachers tried to figure out a way to engage with students.

Initially, she had thought the pandemic shutdowns were going to be a “two-to-three-week thing. But as she saw in-person closures ramping up across the county, she realized it was not going to pass quickly.

“First off, I felt really bad for seniors because they were going to miss out on so many things that seniors get to experience,” she said. “And, of course, I thought ‘What’s going to happen to my profession?’” As the realization of how long the pandemic was going to be dawned on her, Urbanek said her mindset changed, and she realized she was going to really have to change what she was doing in order to help her students.

Urbanek said she does more review with students now, and she’s more willing to change lessons based on what students are struggling with. This is important as she said many of her students missed out on earlier math subjects during the height of the pandemic, and those gaps can be significant.

Urbanek also expressed similar sentiments to Boll over school being seen as less of a priority by students.

“There’s a general mindset that school is no longer my priority,” she said. “My priority is to keep my family safe and keep myself safe,” She’s noticed other challenges as well. Urbanek said many families struggled with all of the roles teachers filled when students went to virtual education.

“Parents relied a lot on teachers,” she said. “Teachers have become more of everything. More of a counselor, more of a tutor, more of a houseworker, sometimes.”

Parents found themselves trying to teach material they have not interacted with in years. They also did not have easy access to school counselors who could assist on mental health challenges.

“Once students were allowed to come back into the classroom, parents were expecting a lot to handle the mental challenges and educational gaps students went through,” she said.

Even with the most extreme moments of the pandemic passed, Urbanek feels a long lasting change to her profession. With the build out of virtual learning, she’s expected to be on the job more now, always checking emails or messages for students in need of help, and receiving staff emails after school hours.

“My day is no longer an eight-hour day,” she said. “It’s 24 hours.”